IN AN ERA where slogans about human rights grow louder, the truth is buried behind prison walls. Palestinian journalist Ameen Baraka, 37, emerges from the rubble of his destroyed home and torment in Israeli prisons to reveal the details of the hell he endured for more than 13 months while detained by Israel, hidden from the eyes of the world.

Baraka worked for several local channels and Al Jazeera; he was arrested in February 2024 from an UNRWA school west of Khan Younis in the southern Gaza Strip. He was released as part of a prisoner exchange deal in February 2025. I visited him and sat beside him near the ruins of his destroyed home, where he shared the harrowing details of his ordeal in Israeli prisons.

When I met Baraka, his face was gaunt, his eyes sunken and shadowed with exhaustion, and his frame noticeably thinner than in the photos I’d seen of him before his arrest. “I lost so much weight,” he confirmed, his voice heavy with fatigue. “We were starved, humiliated and broken, day after day.” His hands trembled slightly as he spoke, a lingering sign of the physical and psychological toll of his captivity.

A DESCENT INTO HELL

Ofer Prison, one of the detention centers in which Ameen Baraka was held. (COURTESY OF AMEEN BARAKA)

“Welcome to hell,” an Israeli intelligence officer sneered at Baraka upon his arrest. What followed was a relentless campaign of torture. “I spent 13 months in Israeli prisons, enduring physical beatings, psychological torment and brutal retaliation,” Baraka recounted. “They subjected me to stress positions, hung me by my wrists and beat me severely. For days on end, I was deprived of sleep, my body and mind pushed to the brink of collapse.”

The physical abuse was merciless. Baraka described how officers tightened their grip around his neck, extinguished cigarette butts on his body and targeted sensitive areas, his testicles, kidneys, stomach, chest and face. “One interrogator shoved my head into a trash bin,” he said, his voice breaking. “They threatened to kill my family, just as they did with the family of Wael al-Dahdouh, Al Jazeera’s Gaza correspondent.”

The psychological torment was equally devastating. One officer mocked him: “We bombed your house with a missile. When you return to Gaza, you’ll have nowhere to live.” Baraka only learned after his release that his home had indeed been completely destroyed and that two of his brothers had been martyred.

The prisons were overflowing with Palestinians, thousands of them, according to Baraka. “I was held with students, journalists, lawyers, human rights activists, engineers, doctors, nurses, academics, lawmakers and workers,” he said. He listened to the testimonies of fellow detainees, many of whom were released in the same exchange deal. They described a range of tortures: electric shocks, severe beatings to sensitive body parts, and even amputations. “Mahmoud Abu Ta’ima had one of his fingers cut off by an intelligence officer,” Baraka recalled. “Thabit Abu Khatar, from Khan Younis, lost his foot.”

Baraka himself endured unimaginable cruelty. “My left leg was tied to a metal corner, my right hand to another, leaving me suspended at an angle while the officer beat me for hours,” he said. The sounds of torture were inescapable. “I heard the screams of other prisoners being tortured in nearby rooms—cries of pain that haunted me day and night, reminding me of the fate awaiting me.”

STARVATION AND HUMILIATION

Food was a tool of punishment. “We were given a small piece of bread and a 250-ml bottle of water to share among ten people, for the entire day,” Baraka explained. The guards deliberately starved them, sometimes stepping on the meager rations or pouring filth over the food. Meanwhile, the smell of grilled meat wafted through the air as prison guards held near-daily barbecue parties near the detention areas, feasting on lavish meals and drinks while the prisoners starved.

Hygiene was another casualty. “We were denied basic necessities,” Baraka said. “We couldn’t clean ourselves or the bathrooms for days.” The lack of sanitation led to the spread of scabies, a skin disease that became another form of torture. “They turned it into a weapon,” he said. “No treatment, no soap, no clean clothes, no sunlight, no regular showers.” The stench in the cells was overwhelming, a constant reminder of their degradation.

Baraka fell ill multiple times during his detention. “I had fevers, stomach pains and infections from the beatings and poor conditions,” he said. Medical care was nonexistent. “At best, sick prisoners got a single paracetamol tablet, no matter the severity of their condition.” The deliberate medical neglect left many in agony, their health deteriorating without relief.

The torture extended to sleep. “They forced us to sleep in a place they called ‘the disco,’” Baraka said. “We had to lie on gravel for 24 hours, on our backs, with a massive speaker next to our heads blaring strange, loud rhythms. It caused stress, anxiety and mental breakdowns.” Sleep deprivation was systematic, guards doused them with cold water, stripped them naked during interrogations and refused to let them rest. “If anyone resisted or challenged the guards, their blood would spill, and their limbs might be severed at the prison’s threshold,” he added.

The days began with violence. “We woke to the sound of batons striking zinc sheets or stun grenades fired at us, signaling a crackdown or transfer to punishment cells,” Baraka said. Even basic needs were weaponized. “We were allowed to use the bathroom once a day, for one minute only. If you exceeded that, they’d beat you and force you to stand with your hands raised for hours, accompanied by insults, punches, kicks and blows from rifle butts and batons.”

SEXUAL ASSAULT AND RELIGIOUS REPRESSION

Among the most horrific abuses was sexual violence. “Soldiers deliberately inserted electric rods and batons into the anal openings of some prisoners,” Baraka recounted, his voice trembling with anger and pain. Guards also unleashed police dogs on detainees, attacking them as they were beaten mercilessly.

Religious expression was stifled. “They banned us from praying or performing our religious rituals,” Baraka said. “No Qur’ans were allowed.” The guards’ actions were a calculated effort to strip them of dignity and hope.

The process of transfer, whether to Israeli courts, between prisons or to interrogation centers, was a journey of torment. “They made us kneel on the ground, hands and feet bound behind us, eyes blindfolded,” Baraka said. “They beat and insulted us throughout.” Legal rights were nonexistent. “We couldn’t defend ourselves or hire lawyers. Visits from family were banned, and we were completely cut off from the outside world: no radio, no TV, no news. During the war on Gaza, I had no idea what was happening to my loved ones.”

Even release brought no relief. “The interrogator threatened to bomb me and my family if I resumed my work as a journalist,” Baraka said. “While I was tied to the interrogation chair, he leaned in and said, ‘You must leave Gaza with your family the moment the Rafah crossing opens, and you’re forbidden from ever returning.’”

A FAILURE OF HUMANITY

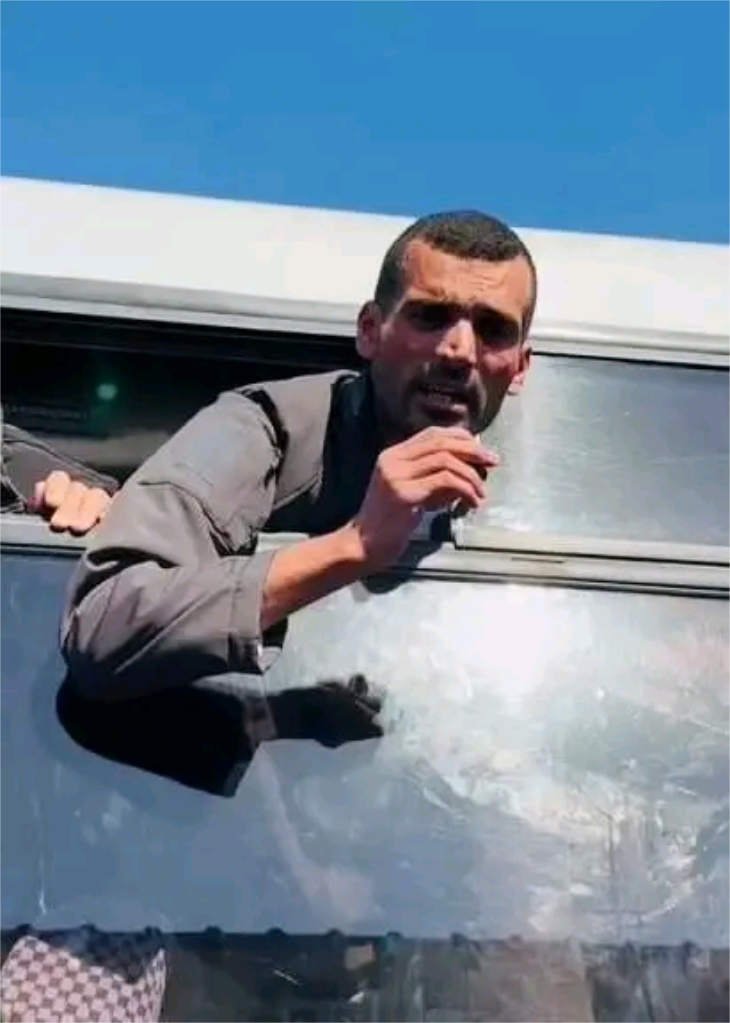

Moments before Ameen Baraka was reunited with his family after his 13-month detention. (COURTESY OF AMEEN BARAKA)

The brutality against Palestinian prisoners constitutes grave violations of international law, yet Israel continues with impunity. Despite being a signatory to the Third Geneva Convention of 1949, which protects prisoners and prohibits torture or humiliation, Israel systematically flouts these obligations. Human rights organizations like Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International have documented Israel’s use of torture against Palestinian detainees, most recently in 2021 and 2023 respectively.

The International Committee of the Red Cross, tasked with monitoring prisoner conditions under the Geneva Convention, failed to act, according to Baraka. “For 13 months, the Red Cross never visited us, never checked our conditions, never provided medical or psychological care, not even food,” he told me. “When we were released, we were shocked to see Red Cross staff for the first time, instructing us to follow Israeli orders not to celebrate or raise victory signs.”

The suffering of Palestinian prisoners defies imagination, and the world’s silence enables it. As I listened to Baraka, his resilience shone through the pain. He looked at me, his eyes fierce with determination, and said, “They tried to break me, my body, my spirit, my voice. But I will not be silenced. I will speak for myself, for my brothers and sisters still in those cells, for Gaza. The world must hear us, see us and act. This is not just my story, it’s the story of thousands, and we demand justice.”